How to Overcome Chronic Pain

If you've been struggling with pain for weeks, months, or years, the worst thing you can do is to continue to move less.

When we feel pain, our instinct tells us to quit moving, to protect that vulnerable area of the body. And while this protective response is sometimes necessary for a short time—especially after a new, acute injury, think rolling your ankle —a harmful pattern emerges when we continue to move less and less. The body becomes more sensitive, amplifying the pain signals. Simultaneously, that protected area grows weaker, progressively limiting your ability to do the things you want to do.

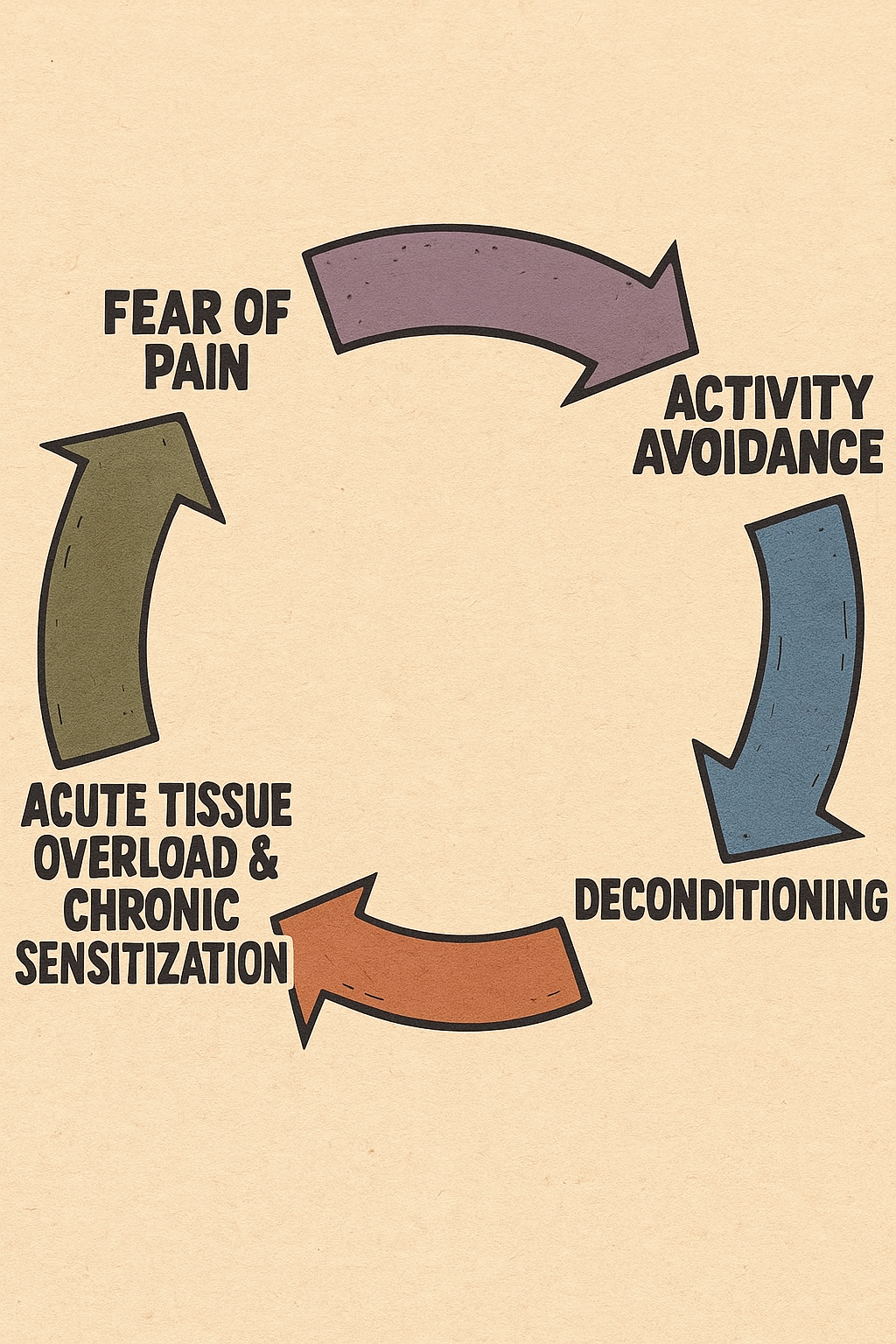

This experience is incredibly common and is known as the pain and disability cycle. In this cycle, pain leads to reduced movement, which causes physical deconditioning and increased sensitivity. This makes even simple activities more difficult and painful, which reinforces the tendency to move less—creating a self-perpetuating loop that progressively worsens over time. The good news is this cycle is one you can get out of, and the feeling of being "stuck" is reversible. The path to feeling better isn't through prolonged rest, but through strategic and consistent movement, often starting with gentle movements.

So what's the better option than rest?

Finding what you can do and starting to do a little bit more each week.

This approach is an evidence-based strategy grounded in a deep understanding of how pain, especially chronic pain, actually works. When pain persists for months, it fundamentally transforms from a simple, protective signal of tissue damage into a complex, self-perpetuating problem within the nervous system itself.

To understand why this solution is so effective, we first need to understand the two interconnected problems that prolonged rest creates: the "sensitive" body and the "weaker" body.

The Two-Headed Dragon: Why Moving Less Makes Pain Worse

Inactivity is a powerful driver of chronic pain precisely because it simultaneously attacks both the body's "software" (the nervous system) and its "hardware" (the muscles and joints). Let's examine each head of this dragon.

1. The "More Sensitive" Problem: Your Brain's Alarm System Gets Stuck on High

This hypersensitivity is a real, measurable neurobiological phenomenon called Central Sensitization.

Think of your nervous system as a home alarm. With acute pain—like a new injury—the alarm sounds when someone breaks a window. It's a helpful, proportionate response to actual tissue damage.

However, in a state of chronic pain, this alarm system gets fundamentally rewired to become hypersensitive. Through a process of "maladaptive neuroplasticity"—the brain's ability to "learn" and reinforce pain pathways—the alarm's "sensitivity knob" gets turned all the way up and becomes stuck there.

This isn't "in your head"; it's a physical change in your nervous system that manifests in two distinct ways:

Hyperalgesia: A stimulus that is normally painful is perceived as more painful.

Allodynia: A stimulus that is not normally painful, like the light touch of a shirt or a gentle stretch, is now perceived as pain.

This hypersensitive state involves changes in the central nervous system, including alterations in how pain signals are processed and modulated. When you stop moving, your brain never receives new, "safe" information to challenge this heightened state, so the sensitivity knob stays stuck on high.

2. The "Weaker" Problem: The Cycle of Fear and Deconditioning

While your nervous system is becoming hypersensitive, your physical body is simultaneously getting weaker—and these two processes fuel each other in a devastating feedback loop. This physical deterioration is part of a well-established framework called the Fear-Avoidance Model.

The cycle unfolds like this:

Pain: You experience pain during a movement (e.g., bending over).

Catastrophizing: You interpret this pain as a sign of serious damage ("My back is fragile," "That movement is harmful").

Fear: This interpretation leads to a debilitating fear of movement, known as "kinesiophobia".

Avoidance: You logically begin to avoid that movement and other "risky" activities to prevent more pain.

Disuse and Deconditioning: This is where the critical physical breakdown occurs. The muscles, tendons, and joints in your back, now systematically unused, become stiff, weak, and far less resilient.

This creates a decreased "Load Capacity." Every tissue in your body has a certain threshold for handling physical load. When you stop moving, this capacity plummets. Now, an everyday task that was once perfectly manageable—like picking up a bag of groceries—suddenly exceeds your body's diminished capacity. This triggers a pain flare, which seemingly "confirms" your original fear that movement is dangerous, and the vicious cycle repeats. Each painful experience leads to more fear, which then leads to avoiding more activities creating more decondition, then eventually more pain, then leaving you more sensitive than before.

How to Break the Cycle: "Finding What You Can Do"

Now that we understand this two-headed dragon—the hypersensitive nervous system and the deconditioned body—we can see why the solution of "finding what you can do and starting to do a little bit more each week" is so remarkably effective. This approach doesn't just address one problem; it simultaneously attacks all of these interconnected issues through three powerful mechanisms.

Mechanism 1: The "Software Fix" (Retraining Your Brain)

At its core, this strategy employs a powerful therapeutic technique known as Graded Exposure Training (GET). It's a "software fix" for your brain that combines behavioral and physical reconditioning to break the fear-avoidance cycle.

The process works like this: First, you identify which specific activities or movements you're most afraid of—these are your "feared stimuli." Then, you gradually expose yourself to these activities in a systematic, controlled way so you can experience firsthand that they're actually safe to perform.

The key is shifting from a "pain-contingent" approach to a "time-contingent" or "quota-based" approach:

Pain-Contingent (The Trap): "I'll walk until my back hurts."

Time-Contingent (The Solution): "Today, I will walk for 5 minutes. Tomorrow, 5 minutes. The day after, 6 minutes."

You set specific, achievable quotas (like "5 minutes of walking") that start below your pain threshold to ensure success. These quotas are systematically increased over time until you reach your goal. The critical difference is that you're progressing based on time or repetitions—not on pain levels. This approach provides direct evidence to your brain that the feared movement doesn't cause the catastrophic harm you expected, which is far more powerful than simply being told that movement is safe. As you successfully complete each exposure without disaster, you systematically unlearn the fear, reduce kinesiophobia, and begin to dial down that stuck sensitivity knob. This isn’t just pain relief, it’s literally rewiring your nervous system.

Mechanism 2: The "Hardware" Fix (Rebuilding Your Body Through Progressive Overload)

While you're retraining your brain, you're simultaneously triggering a "hardware fix" in your physical tissues through the principle of progressive overload. This fundamental concept explains how your body adapts and grows stronger: when you consistently apply a load to your tissues and gradually increase this load the tissues respond by building greater capacity to handle that stress.

A place to start especially when there is a flare up of pain is with gentle mobility exercises that progress to body weight exercises. The gentle movements early on ride on the back of graded exposure letting us get comfortable with movement and then these movements can be made to be more challenging by changing the tempo of the movement, adding weight to the movement or even adding instability to the movement.

Strength training is the most direct application of progressive overload. By systematically challenging your muscles with increasing resistance, you make them progressively more robust and resilient. As your tissues build capacity, activities that once exceeded your threshold and triggered pain—like lifting groceries or bending to tie your shoes—now fall comfortably within your capabilities. Strengthening the muscles around a painful area also enhances joint stability and distributes load away from sensitive structures.

The beauty of progressive overload is that it directly reverses the deconditioning cycle. By starting with manageable loads and incrementally increasing them each week, you're giving your muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints the precise stimulus they need to rebuild their strength and resilience—essentially raising your body's "load capacity" back to functional levels while simultaneously helping to relieve pain.

The principle underlying all of this is simple but powerful: capacity is built through consistent, progressive challenge. Each week's small increase in load provides the stimulus for adaptation, gradually rebuilding your body's ability to handle the demands of daily life without triggering pain.

Mechanism 3: The "Chemical" Fix (Activating Your Internal Pharmacy)

Perhaps most powerfully, consistent movement unlocks your body's own sophisticated, built-in pharmacy—a natural painkilling system that rivals any medication. This phenomenon is called Exercise-Induced Hypoalgesia (EIH), which is the reduction in pain sensitivity that occurs during and after exercise. While this system can be sluggish initially with chronic pain, finding the right 'entry point' movements is key to helping turn it back on over time.

When you exercise, you trigger a flood of natural painkillers throughout your system:

Endogenous Opioids (Endorphins): Exercise stimulates the release of β-endorphins, the body's natural morphine-like compounds. These bind to opioid receptors in key pain-modulating brain regions, providing potent, natural relief. Even better, regular exercise can "up-regulate" this entire system, making your body progressively better at managing pain around the clock.

Endocannabinoids: Often credited with the famous "runner's high," endocannabinoids are molecules your body produces that are remarkably similar to the active compounds in cannabis. They're released during moderate-intensity exercise and are exceptionally effective at reducing both pain and anxiety—directly tackling both the sensory and emotional components of the chronic pain cycle.

Systemic Anti-Inflammatories: Regular aerobic exercise functions as a powerful systemic anti-inflammatory agent. It helps "cool down" the entire nervous system by reducing the pro-inflammatory chemicals that fuel central sensitization and keep that alarm system stuck on high.

Chronic Pain Doesn't Have to Be a Life Sentence

Your body is not broken; it is stuck in a highly intelligent, but ultimately maladaptive, protective loop. The pain is real, the sensitivity is real, and the weakness is real. But equally real is your body's remarkable capacity to change.

By starting small and finding what you can do, you're not just moving, you're engaging in a comprehensive therapeutic program that works on every level simultaneously.

You are:

Retraining your brain to unlearn fear through graded exposure (The "Software" Fix)

Rebuilding your body to be stronger and more resilient through progressive overload (The "Hardware" Fix)

Resetting your chemistry with a cocktail of natural, powerful painkillers (The "Chemical" Fix)

This is how you break the cycle. This is how you reclaim your life, one small, deliberate movement at a time - and this is one aspect of care at Optimize Chiropractic.

If you’re someone who is stuck in the loop of chronic pain and looking for a way out click below to schedule your complimentary consultation to find out how we can help you.

References

Alcon C, Krieger C, Neal K. The Relationship Between Pain Catastrophizing, Kinesiophobia, Central Sensitization, and Cognitive Function in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain. Clin J Pain. 2025;41(7):e1293. Published 2025 Jul 1. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000001293

Baller EB, Ross DA. Your System Has Been Hijacked: The Neurobiology of Chronic Pain. Biol Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 15;82(8):e61-e63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.009. PMID: 28935098; PMCID: PMC5725747.

Ghanbari A. Beneficial Effects of Exercise in Neuropathic Pain: An Overview of the Mechanisms Involved. Pain Res Manag. 2025;2025:3432659. Published 2025 Feb 25. doi:10.1155/prm/3432659

González-Iglesias M, Martínez-Benito A, López-Vidal JA, Melis-Romeu A, Gómez-Rabadán DJ, Reina-Varona Á, Di-Bonaventura S, La Touche R, Fierro-Marrero J. Understanding Exercise-Induced Hypoalgesia: An Umbrella Review of Scientific Evidence and Qualitative Content Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(3):401. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030401

Ji RR, Nackley A, Huh Y, Terrando N, Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and Central Sensitization in Chronic and Widespread Pain. Anesthesiology. 2018 Aug;129(2):343-366. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130. PMID: 29462012; PMCID: PMC6051899.

Koltyn KF, Brellenthin AG, Cook DB, Sehgal N, Hillard C. Mechanisms of exercise-induced hypoalgesia. J Pain. 2014;15(12):1294-1304. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.006

Lima LV, Abner TSS, Sluka KA. Does exercise increase or decrease pain? Central mechanisms underlying these two phenomena. J Physiol. 2017;595(13):4141-4150. doi:10.1113/JP273355

Nijs J, Kosek E, Van Oosterwijck J, Meeus M. Dysfunctional endogenous analgesia during exercise in patients with chronic pain: to exercise or not to exercise?. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES205-ES213.

Stagg NJ, Mata HP, Ibrahim MM, et al. Regular exercise reverses sensory hypersensitivity in a rat neuropathic pain model: role of endogenous opioids. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(4):940-948. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210f880