A Wandering Mind & Happiness

You're sitting in traffic, but mentally you're replaying that awkward conversation from yesterday.

You're folding laundry, but your mind is racing through tomorrow's to-do list.

You're in the middle of a workout, but you're thinking about what you'll eat for dinner.

If this sounds familiar, you're not alone.

A groundbreaking 2010 study from Harvard researchers Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert made headlines with a provocative finding: our minds wander nearly half the time we're awake, and when they do, we're significantly less happy. The implication seemed clear, a wandering mind is an unhappy mind.

But as often happens in science, the full story is more nuanced than the headline. Recent research has revealed that not all mind wandering is created equal, and the relationship between where our attention goes and how we feel depends on several critical factors that the original study didn't capture.

This isn't about judging yourself for getting distracted. It's about understanding how your mind works, when mind wandering serves you, when it doesn't, and what you can do about it.

The Study That Started the Conversation

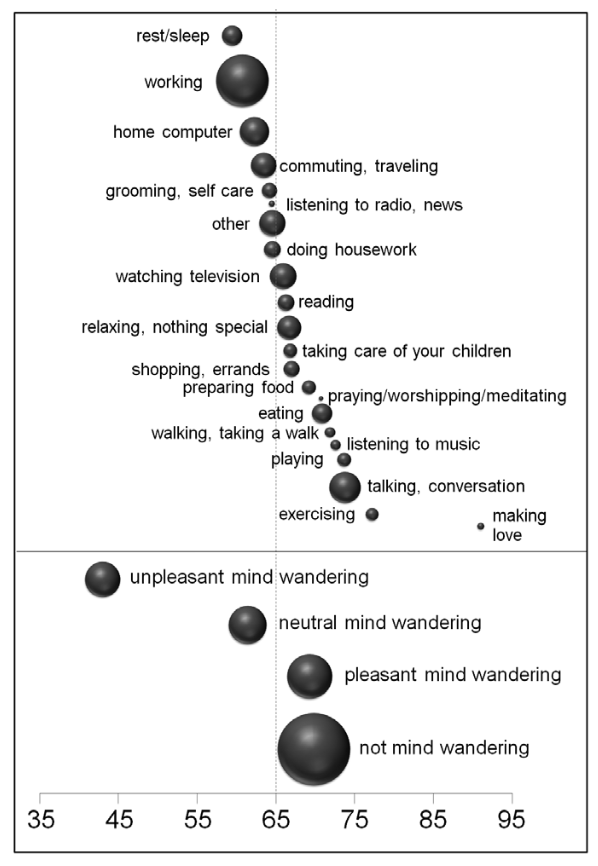

“35-95” represents a happiness scale.

Using an iPhone app, Killingsworth and Gilbert tracked over 2,250 people as they went about their normal lives. At random moments throughout each day, participants received a ping asking three simple questions:

How are you feeling right now?

What are you doing?

And are you thinking about something other than what you're currently doing?

The dataset they collected was massive: nearly a quarter million real-time snapshots of human experiences from people across 83 countries, ranging from age 18 to 88, representing every major occupation category.

Their first finding, people's minds wandered 46.9% of the time. Nearly half of our waking hours we are thinking about something other than what's happening right now. This happened during almost every activity they tracked, with only one exception, making love.

Their second finding generated the headlines, people were significantly less happy when their minds were wandering compared to when they were focused on their current activity. This was true across the board, even during activities people didn't particularly enjoy. Even when people were thinking about pleasant things, they were no happier than when focused on the present moment.

The researchers' conclusion, "A human mind wanders a lot, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind."

But the Story Is More Complex

If mind wandering makes us unhappy, why do we spend nearly half our waking hours doing it? And why does our brain seem designed to operate this way?

These questions prompted researchers to look more carefully at what's actually happening when our minds wander. What they've discovered over the past decade reveals a far more nuanced picture: the relationship between mind wandering and wellbeing depends on when it happens, why it happens, and where our thoughts go.

Three key factors determine whether mind wandering helps or hurts us: intentionality, context, and content.

Factor 1: Intentional vs. Unintentional Mind Wandering

One of the most important recent discoveries is that mind wandering isn't always accidental.

Research by Paul Seli and colleagues has shown that between 34% and 41% of the mind wandering people report in laboratory studies is intentional. People deliberately choose to let their minds drift, even when they're supposed to be focused on a task.

This distinction matters because intentional and unintentional mind wandering behave very differently.

Unintentional mind wandering is what most of us think of when we hear the term, your attention gets hijacked despite your best efforts to stay focused. You're reading a page and suddenly realize you haven't absorbed a single word. You're in a meeting and catch yourself drifting off mid-sentence. This type of mind wandering is associated with attention-deficit symptoms, lower working memory capacity, and greater difficulty with cognitive control.

Intentional mind wandering is different. This is when you deliberately choose to think about something else because the task doesn't demand your full attention, or because you've decided that thinking about something else is more valuable in that moment. You're folding laundry and decide to use the time to mentally plan your weekend. You're on a long drive and purposefully reflect on a problem you've been working through.

Here's what's particularly interesting. These two types respond differently to the same situations. When researchers made tasks more difficult, people reported less intentional mind wandering but more unintentional mind wandering. In other words, when the task got harder, people tried to focus but struggled to maintain attention. When the task was easy, people chose to let their minds wander because they could afford to.

The implications are significant: If you're struggling with persistent mind wandering during tasks that matter to you, that's likely unintentional and may benefit from specific attention-training approaches. If you find yourself deliberately tuning out during tasks, that's a different issue, one that might be more about motivation, the task at hand, or how you're using your mental energy throughout the day.

Factor 2: Context Matters

Researchers Jonathan Smallwood and Jessica Andrews-Hanna have demonstrated something crucial when it comes to mind-wandering, the costs and benefits of mind wandering depend heavily on when it happens.

Mind wandering during demanding tasks that require continuous attention carries real costs. When your mind drifts while you're driving, reading something important, or in the middle of a complex work task, you're more likely to make errors, miss critical information, and perform poorly. Research shows that mind wandering during reading comprehension tasks, working memory tests, and other cognitively demanding activities consistently predicts worse performance.

But mind wandering during non-demanding tasks is a different story entirely.

When the task at hand doesn't require your full attention, when you're doing something routine, simple, or practiced, mind wandering is associated with several benefits. People who mind-wander more during easy tasks show greater creativity, better long-term planning abilities, and more patience in decision-making. They're not failing to pay attention; they're using their cognitive resources efficiently by thinking about things that matter to them while handling tasks that don't require full focus.

This helps explain an apparent paradox, if mind wandering makes us unhappy, why do we do it so much? The answer is that our brain isn't malfunctioning. It's conserving energy. When the environment doesn't demand our full attention, our minds are free to work on other problems; planning our futures, solving complex issues, making sense of our past experiences, and considering our goals.

The key is context. People with better cognitive control don't necessarily mind-wander less overall. They mind-wander less during demanding tasks and more during non-demanding ones. They're better at matching their mental focus to the demands of the situation.

Factor 3: Content Matters

Not all mind wandering is created equal in terms of what you're thinking about.

The content of your thoughts during mind wandering significantly influences whether the experience is helpful or harmful.

Future-focused, planning-oriented mind wandering tends to be adaptive.

When people's minds wander to future goals, upcoming events, or problems they're working to solve, this type of mental time travel serves important functions. It helps us prepare for what's ahead, make better decisions, work through complex problems, and maintain our sense of identity across time. Research shows this type of mind wandering is associated with positive mood and better life outcomes.

Past-focused, ruminative mind wandering, especially when it involves negative themes, tends to be maladaptive.

When mind wandering takes the form of repetitive, negative thoughts about the past, it's associated with lower mood, anxiety symptoms, and depression. This is particularly true when the content involves repetitive dwelling on problems without generating solutions, or when it involves negative self-evaluation.

Recent studies have shown that when people's minds wander to past events, they report a more negative mood afterward. But when their minds wander to the future, their mood becomes more positive. Similarly, when people rate their mind wandering thoughts as interesting or engaging, their mood improves rather than declines.

This distinction is crucial for understanding the original Killingsworth and Gilbert findings. Their study showed that mind wandering in general is associated with unhappiness, but they didn't distinguish between future-oriented planning and past-oriented rumination. More recent research suggests that much of the unhappiness associated with mind wandering may be driven by specific patterns of negative, repetitive thought rather than by mind wandering itself.

Mind Wandering Serves Important Functions

Understanding these nuances helps us see that mind wandering isn't simply a failure of attention. It's a fundamental feature of the human brain that serves important adaptive functions.

Mind wandering allows us to engage in mental time travel, to connect our past experiences with our future goals and our current identity. It provides space for creativity and insight, often leading to solutions that wouldn't emerge through focused analysis alone. It helps us consolidate memories and integrate recent experiences into our broader understanding of ourselves and our lives.

The ability to think about what isn't happening right now is, in fact, one of humanity's greatest cognitive achievements. No other species can do this quite the way we can. This capacity for mental time travel allows us to learn from the past and prepare for the future in ways that have been crucial to human survival and success.

The challenge isn't to eliminate mind wandering. The challenge is to develop greater awareness of when it's happening, whether it's serving you, and the ability to guide your attention more intentionally.

Training Your Attention: The Mindfulness Connection

One of the most practical findings from recent research is that the relationship between mind wandering and attention can be trained.

In a study by Michael Mrazek and colleagues, participants completed just two weeks of mindfulness training, eight 45-minute classes focused on developing present-moment awareness. Compared to a control group who received nutrition training, the mindfulness group showed the following significant improvements:

Working memory capacity increased

GRE reading comprehension scores improved by an average of 16 percentile points

Mind wandering decreased across all three measures (probe-caught, self-caught, and retrospectively reported)

Importantly, the improvements in performance were influenced by the reduction in mind wandering. In other words, participants performed better because they were better able to stay focused when focus mattered.

The mindfulness training used in this study focused on several key practices: maintaining an upright posture, learning to distinguish between naturally arising thoughts and elaborated thinking, using the breath as an anchor for attention, and allowing the mind to rest rather than suppressing thoughts.

This research doesn't suggest that mindfulness eliminates mind wandering or that it should. Rather, it suggests that mindfulness practice can help you develop greater control over your attention—the ability to stay focused when tasks demand it and the awareness to notice when your mind has wandered.

Other interventions have shown promise as well:

Making concrete plans to address unfulfilled goals can help reduce distracting thoughts.

Highlighting important information helps sustain attention.

Simple awareness of mind wandering patterns can help people develop more effective strategies for managing their attention.

What This Means for Your Daily Life

So what do you do with this more nuanced understanding?

First, recognize that not all mind wandering is problematic. If your mind drifts while you're doing routine tasks and you find yourself thinking through plans, working on problems, or considering your goals, that's your brain working as designed. You don't need to fight it, and in fact, allowing this kind of mental space can be valuable.

Second, pay attention to context. Notice when your mind tends to wander during tasks that actually require your focus, reading something important, having a meaningful conversation, working on a complex project. These are the moments when mind wandering carries real costs. This is where attention training might be most valuable.

Third, notice the content of your mind wandering. Are you planning, problem-solving, and thinking about the future? Or are you caught in repetitive loops of negative thinking about the past? The former tends to be adaptive; the latter often isn't. If you notice patterns of negative rumination, that's worth addressing, not by trying to eliminate mind wandering, but by working with the content and patterns of your thoughts.

Fourth, consider your level of intention. Are you deliberately choosing to think about other things, or is your attention being pulled away despite your best efforts? If it's the latter, and if it's interfering with things that matter to you, that's worth addressing through attention training, better task design, or changing your environment to support focus.

Fifth, if you're interested in developing greater control over your attention, mindfulness practice has solid evidence behind it. Even short daily practices, 10 minutes of focused attention on your breath, body sensations, or present-moment experience, can begin to shift your relationship with your attention over time.

The Bigger Picture

The original finding that mind wandering is associated with unhappiness was important, but it wasn't the whole story.

Mind wandering isn't a simple failure that needs to be eliminated. It's part of the complex inner-workings of our brain that can serve us well or poorly depending on when it happens, why it happens, and where our thoughts go. The same cognitive system that allows our minds to wander away from boring tasks also enables us to plan our futures, solve complex problems, and maintain our sense of who we are across time.

The goal isn't to achieve some perfect state of constant presence. The goal is to develop greater awareness of your attention, greater skill in directing it when needed, and greater wisdom in recognizing when your wandering mind is serving you and when it isn't.

Your life is happening right now. But your capacity to think about what isn't happening, to remember your past, imagine your future, and work through complex problems, is part of what makes you human. The question isn't whether to let your mind wander. The question is whether you're wandering with intention, in situations where you can afford it, and in directions that are beneficial.

Developing the capacity to work skillfully with your attention, to stay present when presence matters and to let your mind roam productively when it can, may be one of the most impactful things you can do for your cognitive performance and your quality of life.

Stay present when it matters, and let your mind wander wisely when it can.

▸ Click to view Scientific References & Evidence

Primary Mind-Wandering Research

- Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science. 2010;330(6006):932.

Intentional vs. Unintentional Mind Wandering

- Seli P, Risko EF, Smilek D, Schacter DL. Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(8):605-617.

- Seli P, Risko EF, Smilek D. On the necessity of distinguishing between unintentional and intentional mind wandering. Psychol Sci. 2016;27(5):685-691.

Context and Content of Mind Wandering

- Smallwood J, Andrews-Hanna JR. Not all minds that wander are lost: The importance of a balanced perspective on the mind-wandering state. Front Psychol. 2013;4:441.

- Baird B, Smallwood J, Schooler JW. Back to the future: Autobiographical planning and the functionality of mind-wandering. Conscious Cogn. 2011;20:1604-1611.

Mindfulness Training and Mind Wandering

- Mrazek MD, Franklin MS, Phillips DT, Baird B, Schooler JW. Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(5):776-781.

Supporting Research on Default Network and Cognition

- Raichle ME, et al. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:676-682.

- Christoff K, Gordon AM, Smallwood J, Smith R, Schooler JW. Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8719-8724.

- Smallwood J, Schooler JW. The restless mind. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:946-958.