Why "Getting Back to Normal" Isn't Enough

You've been here before.

You got hurt. You rested, maybe saw someone and did what you were supposed to do. The pain settled. You felt better. You went back to your life.

And then, weeks later, months later, you got hurt again. Maybe the same area, maybe the same activity, maybe something that shouldn't have been a big deal at all. And now there's this thought that won't quite leave: this is just part of getting older.

The thought makes sense. When the same problem keeps coming back, there has to be an explanation. You are older than you used to be. This might just be what life looks like from here on out.

But there's another possibility worth considering. One that doesn't match the typical "it's just part of getting older" story but does explain why recovery didn't stick.

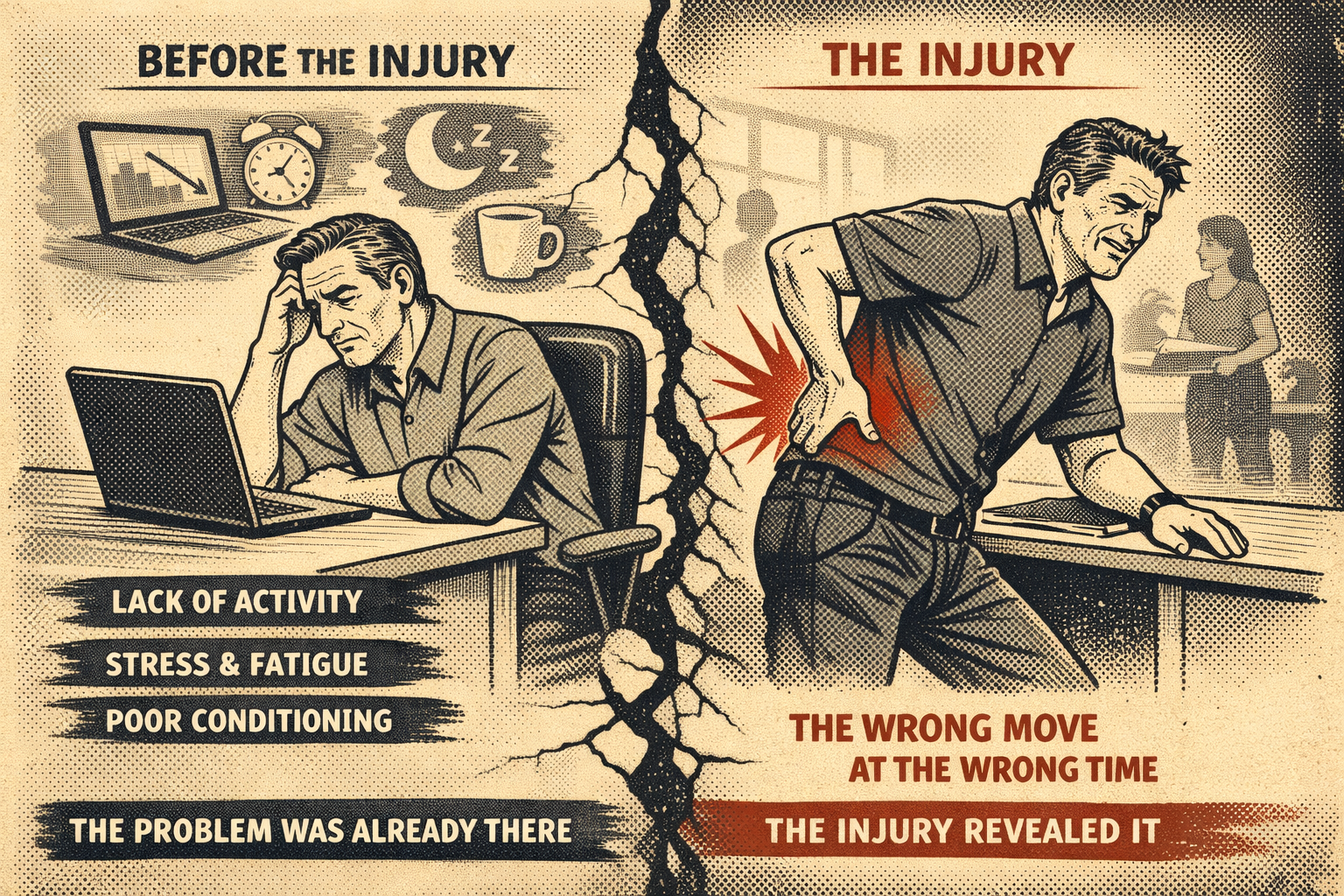

The Injury Wasn't the Beginning of the Problem

When we get injured we typically think, “What I just did caused the injury, so I need to avoid that movement or activity or I'm likely to get hurt again.”

Maybe you spent the winter moving less than you did in the summer. Maybe work got busy and the gym fell off. Maybe stress and bad sleep quietly chipped away at what you could do without you noticing. Or maybe nothing dramatic happened at all—you just hadn't been moving that area in the way the task demanded, and it was never really prepared for it.

Then came the moment: the twist, the bend, the reach, the thing you'd done a hundred times before. Except this time it hurt.

The natural thought is, this specific movement caused the injury. Something went wrong right then. But often, the movement just revealed a mismatch that already existed, between what the body was being asked to do and what it had actually been prepared to handle.

The injury was the first time you found out about the mismatch. It wasn't the first time the mismatch was there.

What "Getting Back to Normal" Actually Means

When care focuses only on resolving pain; getting the inflammation down, getting you moving again, getting you back to your life, there's an assumption underneath it.. Before the injury was fine, and the goal is to return there.

But if the vulnerability existed before the pain did, then "back to normal" can mean back to where you were when you got hurt.

Same strength. Same capacity. Same gap between what you can handle and what your life asks of you. The mismatch that created the problem is still there. It's just quiet again.

This is often why people end up in cycles. They recover. They return to activity. They get hurt again, often doing something similar, often feeling blindsided by it. When it keeps happening, the explanation that makes the most sense is: I'm just older now. This is what happens.

That story is comfortable in a way. There's nothing to be done about time. If aging is the cause, then the decline is inevitable and you're off the hook for changing anything.

However, much of what we call "aging" is actually deconditioning. It's not that time wore your body down, it’s that over the years, you moved less. Loaded less. Asked less of your tissues. And they adapted to exactly what you gave them.

The body that got hurt at 52 wasn't worse because it was 52. It was because it had been doing less for longer. The capacity gap widened not because of birthdays, but because of what happened between them.

This is better news than the aging story because deconditioning isn't inevitable. It's reversible.

What Recovery Should Look Like Instead

The goal isn't to get back to where you were. That's where most treatments stop and it's why so many people end up cycling through the same problem, assuming this is just the way it is now.

The goal is to build past it.

To end up stronger than the task that hurt you. To develop capacity that wasn't there before, because "before" was never actually enough.

The person who hurt their back putting up holiday decorations doesn't just need the pain to go away. They need a back that can handle twisting on a ladder with their arms overhead. They need to build the capacity that was missing—the strength, the stability, the tolerance for that specific demand—so that next year, the task is well within what their body can do.

The weekend athlete who keeps tweaking something doesn't need to accept that their body can't handle activity anymore. They need to close the gap between what they're asking their body to do on Saturday and what they've prepared it for during the week.

The person at 55 who assumes this is just how it is now doesn't need to learn to live with limitations. They can be genuinely stronger, more resilient, better prepared than they were at 45, not through denial, but through addressing what actually changed.

This takes longer than just waiting for pain to settle. It means building progressively, not just recovering passively. It means treating capacity as the goal, not just the absence of symptoms.

It's what makes recovery actually stick. Not because you got lucky this time, but because you're not the same person who got hurt.

The Real Measure

There's a question that matters more than pain levels or how many birthdays you've had.

Can you do the things you want to do; twist and bend, lift and carry, play with your kids or grandkids, work in the yard, travel, stay active all without assuming that injury is just around the corner?

That's not something that happens when pain fades. It's something that gets built. Deliberately, progressively, over time.

The goal of care isn't to manage decline. It isn't to get you back to a body that was already falling short. It definitely isn't to help you accept that this is just what getting older looks like.

The goal is to build a body that's more capable than the one that got hurt. That's possible at 40, at 55, at 70. Not by ignoring your age, but by refusing to blame it for something it didn't cause.