Understanding Chronic Pain & How to Get Relief

Most of us think of pain as a simple signal:

Something hurts → something is wrong → fix the thing → pain goes away.

If only it stayed that straightforward.

Pain is not simply a sensation in the tissues. It is an output of the brain — a protective alarm designed to warn you of danger. Under normal conditions, that alarm works remarkably well. But in chronic pain, the alarm becomes overprotective. Instead of responding only to real threats, it begins to sound in situations that are no longer dangerous.

Like a fire alarm that goes off when you slightly burn your toast.

This is why the primary driver of chronic pain is often not:

Weak muscles

Bad posture

Or what an MRI happens to show

More often, it’s a nervous system that has learned to stay on high alert.

How Pain Works When the System Is Healthy

Under normal circumstances, pain is protective.

Sensors in the tissues respond to stretch, pressure, and temperature. These signals enter the spinal cord, are processed, and then travel to the brain. The brain then evaluates whether the situation is dangerous enough to require a pain response.

If the answer is yes, you feel pain. You guard, rest, and protect.

As the tissue heals and movement resumes, the nervous system receives repeated safety signals. Over time, the brain updates its evaluation of danger and then overtime turns the alarm back down.

Pain fades because the system has proof that the danger has passed.

One way chronic pain develops is when this update process fails to complete, the system stays sensitized even as tissues heal.

Not only because of ongoing tissue damage, but because the processing system has been remodeled.

Where Pain Becomes Learned: The Spinal Cord

One of the most important changes in chronic pain happens in the spinal cord, particularly in a region called the dorsal horn, which acts as the first major processing center for pain.

When nerves fire repeatedly from the site of injury over long periods of time:

Spinal cord neurons become easier to activate

Chemical messengers that amplify pain increase

Learning receptors reinforce the pathway

This process is called long-term potentiation, the same biological learning mechanism that strengthens skills, habits, and movement patterns.

Except now, it is strengthening pain.

The system becomes faster and more efficient at producing pain, even in response to smaller, non-threatening inputs.

This is why people often say:

“I barely did anything, and my pain flared up again.”

It’s not because the body is fragile.

It’s because the processing center learned to overreact.

What makes this stage so important is that once the spinal cord becomes sensitized, it doesn’t just amplify signals going up to the brain it also sends ongoing messages back down to the initial site of injury.

So even if the tissue itself has healed, the nervous system may still be acting as if the injury is actively happening.

And when the nervous system believes an area is still injured, it keeps certain biological repair processes turned on.

When Safe Inputs Start Feeling Dangerous

When a initial injury occurs a cascade of healing factors rush to the area to help the area recover. One of those factors is called Growth Factor.

Growth factors help nerves and sensors heal and regenerate, a normal and necessary part of the initial phase of healing healing, but these growth factors are not selective. They help everything grow. The touch fibers, the pressure fibers, and the pain fibers. In a normal healing situation this works perfectly but when the processing center at the spinal cord is hyperactive it keeps the healing process turned on and over time, touch fibers, pressure fibers, and pain fibers can begin to share common pathways.

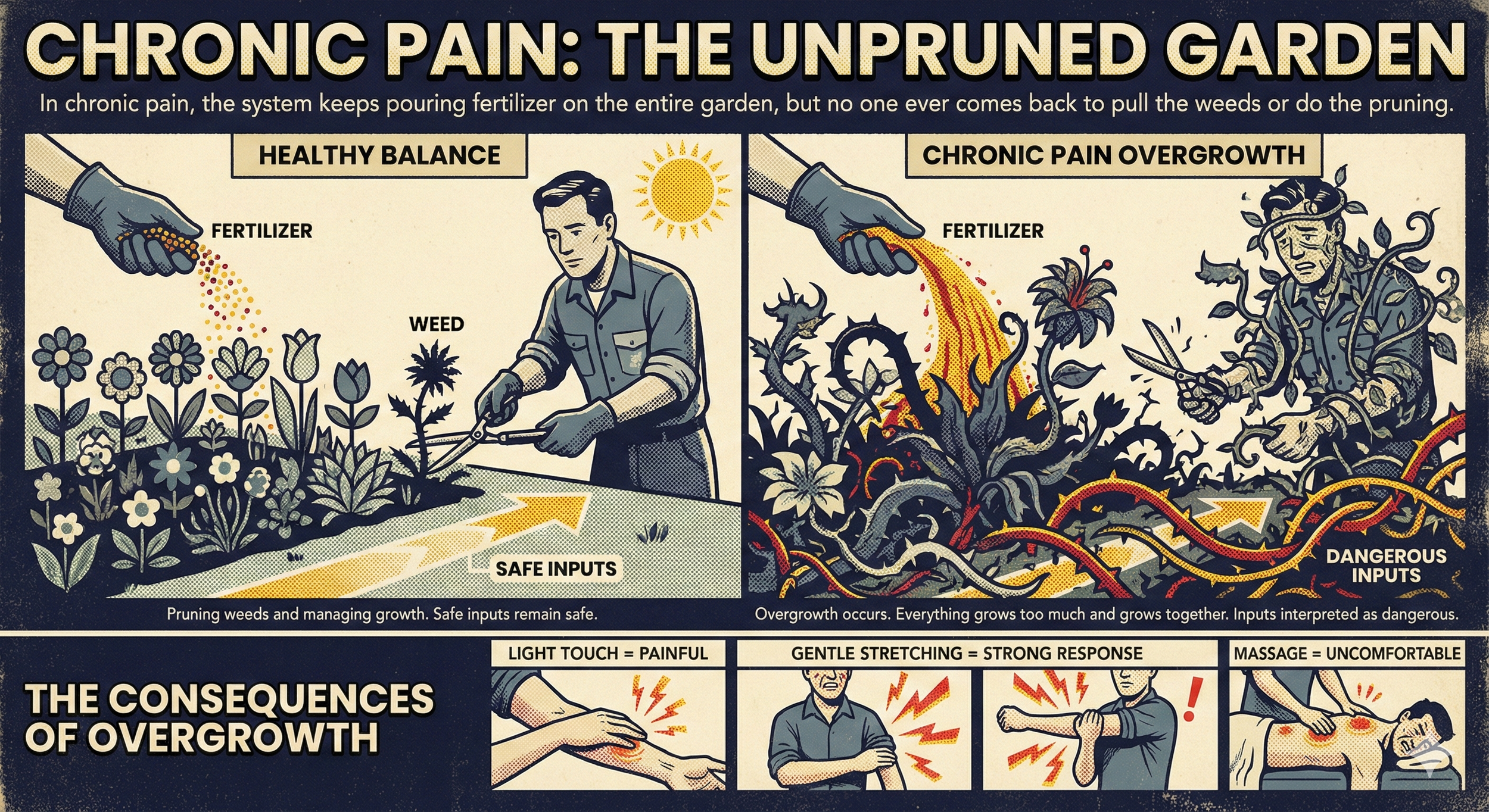

A near-perfect way to think of this is like fertilizing and weeding a garden on a regular schedule.

In the early phase of healing, growth factors are like a light round of fertilizer — they help everything grow a little, which is exactly what you want. But at the same time, the body has other systems in place that act like gardeners: pulling weeds, trimming back overgrowth, and keeping things organized.

In chronic pain, that balance is lost. The system keeps pouring fertilizer on the entire garden every single day — but no one ever comes back to pull the weeds or do the pruning.

Over time, everything grows too much and grows together including the plants you never wanted spreading in the first place.

When this overgrowth occurs inputs that were once interpreted as safe can now be interpreted as dangerous.

This helps explain why:

Light touch can feel painful

Gentle stretching triggers a strong response

Massage that once felt good can feel uncomfortable

These experiences fall under two well-known phenomena:

Allodynia — pain from normally non-painful input

Hyperalgesia — an exaggerated response to mildly painful input

The tissue itself is not suddenly damaged or fragile.

It’s that the wiring changed because the system never got the message that the danger was truly over.

And once those altered signals are being sent over and over again, they don’t just stay at the level of the body.

Over time, these signals begin to reshape how the brain itself interprets movement, sensation, and threat.

How Persistent Pain Reshapes the Brain

The brain is constantly integrating multiple streams of input:

Sensation

Movement

Attention

Emotion

Threat prediction

Its job is to weigh all of that information and answer one central question at all times:

“Is this situation safe, or is it dangerous?”

When signals repeatedly arrive telling the brain that a certain area of the body is injured, even after the tissue has healed, the brain begins to operate under a state of constant perceived threat.

It becomes hyper-focused on that area.

Sensations from that region become louder.

Movement involving that region becomes closely monitored.

Attention narrows toward anything that might provoke symptoms.

Emotion becomes more tightly tied to anticipation of pain.

Threat prediction shifts toward expecting discomfort before it happens.

Over time, this constant vigilance changes how the brain views the body itself.

The brain’s internal map of the painful area begins to lose precision, a process commonly referred to as cortical smudging. Instead of having a clear, well-defined representation of where and how the body is moving, the map becomes blurry and less specific.

This helps explain why people may experience:

Pain that spreads or feels difficult to localize

Stiffness or weakness without clear tissue damage

A loss of confidence and fine control in movement

At the same time, the brain’s prediction system becomes increasingly biased toward danger. It begins to expect pain, and in preparation for that expectation it turns protective outputs on earlier and more aggressively.

This does not mean the brain is damaged.

It means the brain has adapted to persistent threat signals.

And because this adaptation follows the same biological rules as learning, it is also changeable.

Pain is not the output of a failing brain.

It is the output of a brain that has become overprotective.

What This Means for You

Chronic pain is not evidence that the body is “breaking down.”

Most of the time, it reflects:

A hypersensitive alarm system

A spinal cord that has turned up the gain

Neural circuits reinforced through repetition

Protective behaviors that keep the system on edge

Fear that further amplifies the cycle

The pain is real.

But the primary driver is the system, not the structure.

That’s why focusing only on “fixing tissues” so often falls short. When the nervous system has become the main pain amplifier, the solution has to involve the nervous system as well.

How the Nervous System Unlearns Pain

There is no single technique that turns chronic pain off overnight, but there are consistent biological principles that help the system recalibrate.

Graded Movement

Small, controlled, repeated exposures teach the nervous system what is safe again. Over time, tolerance increases and the brain relearns it’s safe. Not through force, but through precision and repetition.

Understanding the Biology

Fear directly increases sensitization. When people understand that pain does not automatically mean damage, the system stops bracing for catastrophe. That alone lowers the volume of the pain response.

Stress Regulation

Chronic stress biases the nervous system toward fear and danger. Tools like breathwork, meditation, and NSDR act as direct way to help re-establish a baseline of safety. This helps with how pain signals are filtered and dampened.

Meaningful Activity

The system recalibrates most powerfully when people return to activities that matter, movement with purpose, social connection, creative work, and valued roles.

Coordinated, Multimodal Support

Chiropractic care, rehab, strength training, and education work best when they operate as coordinated inputs, all teaching the same message: safety, capacity, and confidence.

A More Accurate Story About Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is not the body failing.

It is the body adapting, just not helpfully.

And anything that has been learned can also be unlearned.

Not instantly.

Not forcefully.

But in a way that is predictable, trainable, and grounded in real neuroscience.

Your nervous system can become overprotective.

It can also recalibrate.

That’s where real change begins.

Our clinical approach is supported by current research in pain neuroscience and rehabilitation. Click below to access the full bibliography and source materials.

▸ Click to view Scientific References & Evidence

Core Pain Definition & Threat Model

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Explainer: What is Pain? 2025.

- Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain Pain. 2nd ed. Noigroup Publications; 2013.

- Veterans Affairs. Seven Things You Should Know About Pain (PDF).

- Moseley GL, Arntz A. The context of a noxious stimulus affects the pain it evokes. Pain. 2007;133(1–3):64-71.

Imaging ≠ Pain (Asymptomatic Degeneration)

- Brinjikji W, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(4):811-816.

- Ract I, et al. Value of MRI signs in low back pain. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:S65-S73.

- Vagaska E, et al. Do lumbar MRI changes predict low back pain? Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(17):e15370.

- Flynn TW, et al. Appropriate use of diagnostic imaging in low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(11):838-846.

Central Sensitization & Dorsal Horn LTP

- Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity. J Pain. 2009;10(9):895-926.

- Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization and LTP. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26(12):696-705.

- Ruscheweyh R, et al. Long-term potentiation in spinal nociceptive pathways. Pain. 2011;152(4):743-753.

- Lee KY, et al. Reactive oxygen species in spinal dorsal horn LTP. J Neurophysiol. 2010.

- Tansley SN, et al. Translation regulation in spinal dorsal horn. Neurobiol Pain. 2018.

- JOSPT Editorial. Pain Science in Practice (Part 5): Central Sensitization II. JOSPT. 2023.

Allodynia & Hyperalgesia

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Allodynia and Hyperalgesia Fact Sheet.

- He Y, et al. Allodynia. StatPearls. 2023.

Cortical “Smudging” & Brain Remodeling

- Büntjen L, et al. Somatosensory misrepresentation in CRPS. Neuroimage Clin. 2017.

- Chang WJ, et al. Sensorimotor cortical activity in acute and chronic LBP. Neuroimage Clin. 2019.

- Jenkins LC, et al. Somatosensory cortex excitability predicts chronic pain. J Pain. 2022.

- Apkarian AV, et al. Chronic back pain and gray matter changes. J Neurosci. 2004.

Threat, Stress & Fear Learning

- Vlaeyen JWS, et al. Threat value influences pain expression. Pain. 2009.

- Schlitt F, et al. Impaired threat and safety learning in chronic back pain. Pain. 2022.

- Vachon-Presseau E, et al. Stress model of chronic pain. Brain. 2013.

Graded Exposure & PNE

- Vlaeyen JWS, et al. Graded exposure in vivo for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2001.

- Riecke J, et al. Implementation of graded in vivo exposure. Clin J Pain. 2013.

- Watson JA, et al. Pain neuroscience education for chronic MSK pain. J Pain. 2019.

- Louw A, et al. Revisiting provision of pain neuroscience education. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021.

- Benedict TM, et al. PNE improves PTSD in chronic LBP. 2023.

- Corbo D, et al. Pain neuroscience education and neuroimaging. 2024.

Meditation & Biopsychosocial Rehab

- Morone NE, Greco CM. Mindfulness meditation for chronic LBP. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007.

- Cherkin DC, et al. MBSR vs CBT vs usual care for chronic LBP. JAMA. 2016.

- Hilton L, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017.

- Kamper SJ, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for CLBP. Cochrane Database. 2015.

- Saragiotto BT, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2016.

- IASP. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain.